The University of Hong Kong

May 23 – June 15, 2013

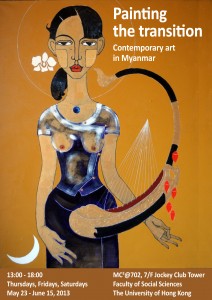

Coming in from the cold after 50 years of austere dictatorship, Myanmar is currently testing the boundaries of a raft of new freedoms. Rigid controls were not dismantled overnight, but a March 2011 switch from military junta to quasi-civilian rule has slowly created space for meaningful self-expression. Finally people can breathe a little.

More than two years on, activists routinely take to the streets of major cities to protest government policy, journalists pursue breaking stories up and down the land, hawkers beguile tourists with long banned symbols of opposition, and ordinary citizens daily raise their sights just a little higher.

Playing critical roles in this outpouring of human creativity and energy are artists and intellectuals never fully silenced by authoritarianism, but certainly forced for years to operate below probing security radars. Today, by contrast, writers give readings at literary festivals, musicians perform rap and hip hop in concert, and painters exhibit canvases that for decades could be shared only with trusted friends.

Growing links with the outside world, dating from the late junta period, were important enablers of this renaissance. The arrival of internet cafes in major cities in the mid-2000s was notably important. Above all, though, change was driven locally as isolated groups of individuals formed for mutual support in teashops and restaurants built integrated and confident networks when political reform gathered pace.

One consequence of Myanmar’s cultural rebirth is that a significant number of artists can now work on a full-time basis. For leading painters, the change has been dramatic. Although the state ruled by generals generated jobs in illustration, graphic design and commissioned pictures for a small tourist trade, few could give free rein to their talent. Today an expanding group does precisely that.

Still conditions are not ideal. Some commercial galleries continue to flirt with state censorship. The major professional association is unreconstructed. The ponderous National Museum is off limits for most contemporary artists. Selling sufficient work to make ends meet is often a challenge. Nevertheless, the range and quality of art now being produced by local painters is astounding.

Accessed from a chipped concrete staircase in a crumbling colonial building, Pansodan Gallery in downtown Yangon is the hub for many new artists. Launched by husband and wife team Aung Soe Min and Nance Cunningham in August 2008, the gallery works proactively to connect painters with each other, and with potential buyers. It is also trying to launch an independent artists’ association.

Within the emergent band of painters some are openly political, espousing membership of a broad opposition movement. For them, independence hero Aung San, democracy icon Aung San Suu Kyi, and monks participating in the 2007 saffron uprising, all taboo topics until very recently, are now standard subjects. So too are oblique references to government failings and social problems.

More common across the new cohort, though, is a dual desire first to connect with the cultural heritage of a major artistic tradition, and second to bring it squarely into the contemporary age of sweeping social and political change. Buddhist symbols and ritual thus feature. Ethnic costume, music and dance are important themes. Customs and habits of village people in a still rural society are carefully represented. Changing rhythms of vibrant urban life are fully documented.

In these diverse ways, painters from Myanmar’s new generation of cultural and intellectual leaders provide nuanced and incisive commentary on a society embarking on what is certain to be a difficult journey. The start point was military dictatorship. The end point is unknown. Capturing twists and turns in the road is a network of accomplished artists emerging from a hermetic state.