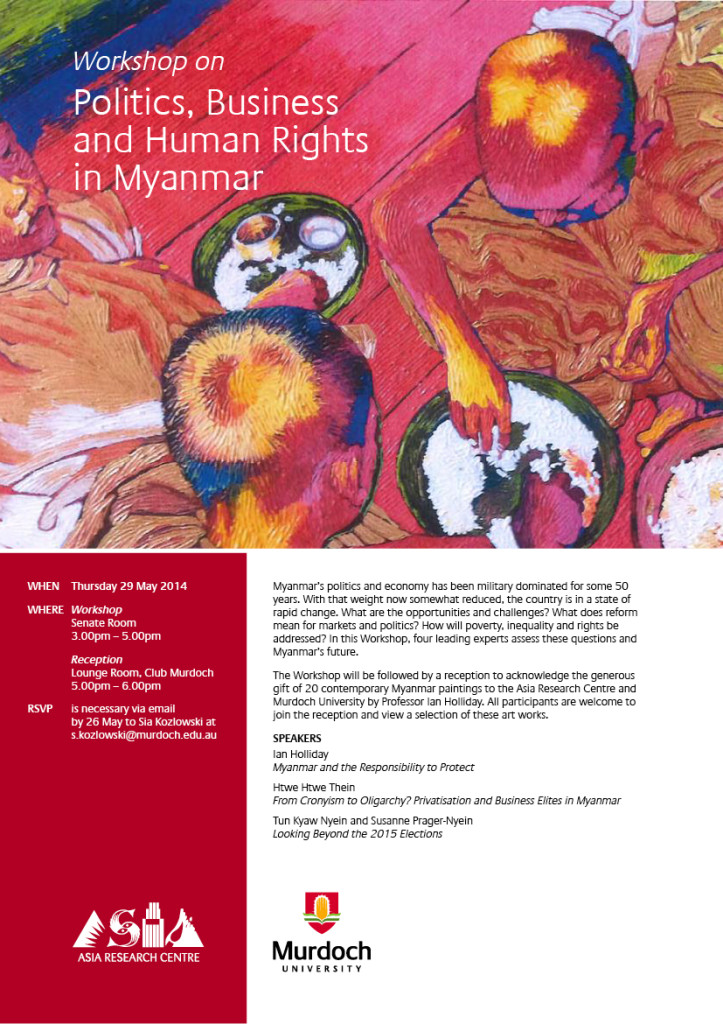

Workshop on Politics, Business and Human Rights in Myanmar

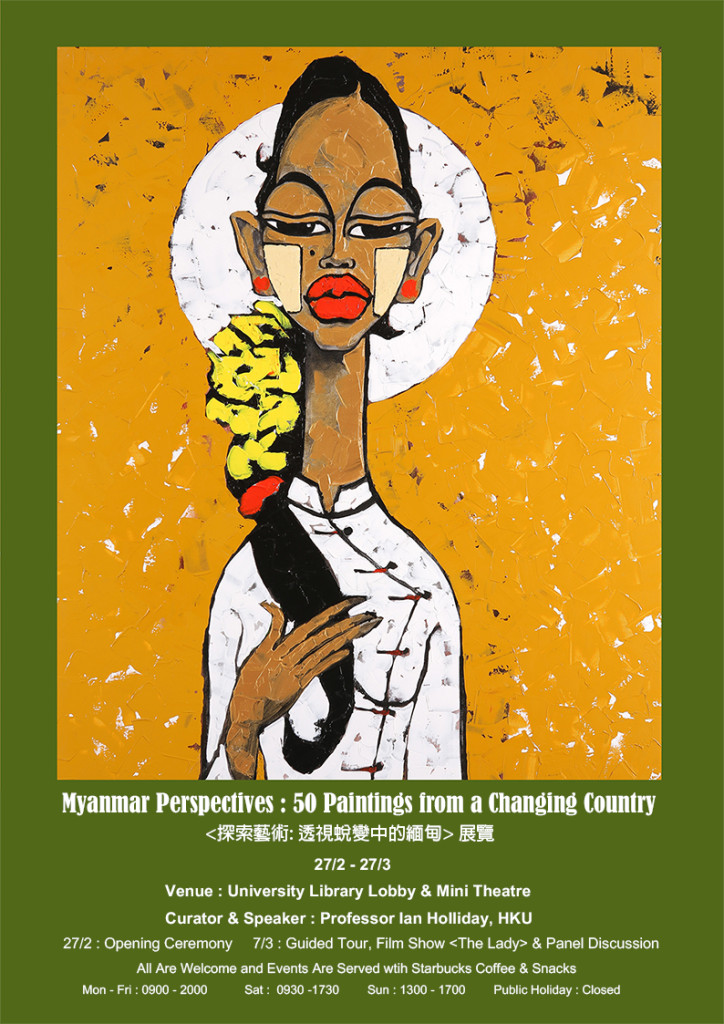

Myanmar Perspectives: 50 Paintings from a Changing Country

Lingnan University

February 27 – March 27, 2014

For three years since the installation of a quasi-civilian government in March 2011, Myanmar has experienced a large number of reforms. At a time when analysts are struggling to assess the political, economic and social significance of those reforms, this exhibition adopts a somewhat different perspective.

Looking through the eyes of more than a dozen contemporary artists, it presents 50 paintings from a changing country. Alongside openly political images, which until very recently would have been banned by state censors, are depictions of daily life in villages and towns during a period of transition, of religious beliefs and symbols, and of disparate ethnic groups and identities.

Together, these paintings, produced in the past couple of years by artists of diverse age, background and interest, constitute an invaluable window onto a dynamic and complex society, and help to trigger new ways of understanding a country that is still largely unknown to the outside world.

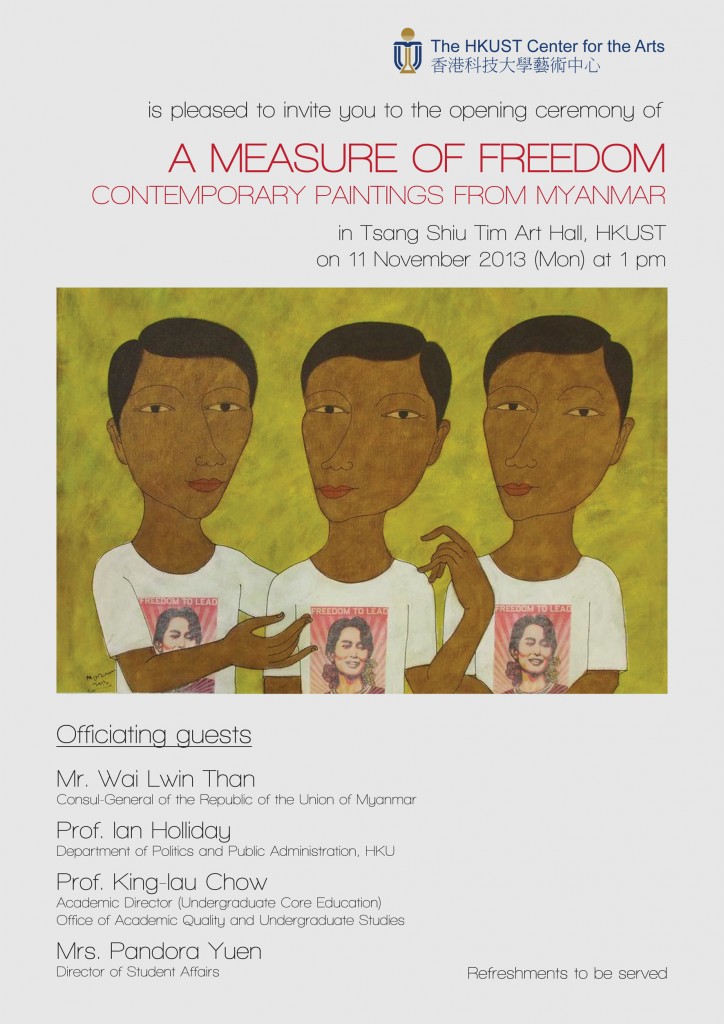

A Measure of Freedom: Contemporary Paintings from Myanmar

The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology

November 11-24, 2013

For most of the recent past, the country known today as Myanmar and until 1989 as Burma was subject to strict authoritarian rule. In 1962, a harsh state socialist regime was instituted with overt military backing. In 1988, collapse of that system at a time of mass protest for democracy resulted only in installation of a formal military junta. Not until 2011 was the junta finally dissolved and control handed to a quasi-civilian government that soon set about implementing a series of major reforms.

Throughout the authoritarian period, draconian censorship was enforced. Printed material was subject to pre-publication vetting, and non-state publishers of books and newspapers (issued only on a weekly basis as journals) were closely monitored. Many appeared with sections blacked out by the censor, and on occasion even cover stories had to be sacrificed. Film and music were checked just as tightly, with scripts and lyrics routinely submitted for review. Paintings and photographs were also brought under the watchful eye of the censor, and all public exhibitions were required to adhere to rigid controls.

The censorship regime faced by creative artists was deeply conservative. Reflecting the spotlight turned on “degenerate” art by the Nazis in the 1930s, nascent modernist tendencies in painting were viewed with extreme suspicion and largely quashed. Provocative subject matter was outlawed. There were also idiosyncratic constraints. In 1988, when Aung San Suu Kyi and her colleagues decided to set the logo of the National League for Democracy on a red field, that colour entered the list of taboos.

A measure of the freedom presently spreading across Myanmar is thus the changed environment now confronting painters. While censorship has not yet been abolished, it currently operates with a very light touch. By and large, there is no serious vetting of art shows today, and painters are able to explore a wide range of subjects using techniques, media and colours that even a few years ago would not have been tolerated inside the country.

Almost all of the paintings presented in this exhibition were completed in the current reform period, as censorship was gradually lifted. The vast majority date from either 2012 or 2013. Together, they provide a snapshot of a critical period in the country’s development. Indeed, when future historians look back on the transition from authoritarian rule, images such as those assembled here will be key primary sources.

Most of the paintings are not explicitly political, though some are. Notably, the work of Min Zaw, Zwe Mon and Zwe Yan Naing has political overtones, with allusions to Aung San Suu Kyi standing alongside a depiction of the 2007 saffron uprising. Similarly, the Buddhist drummers in the work of Kaung Kyaw Khine point to political themes at a time of violent strife in Rakhine State. Just possibly Dawei Lay also makes a political statement, for the bamboo hat featured in his paintings is a potent opposition symbol.

Other artists have more prosaic concerns, focused on contemporary life in villages, towns and cities, and on the religious and other rituals that define everyday existence for many people. Alongside depictions of majority Bamar Buddhist culture are the traditions of minority peoples living mostly in peripheral parts. Next to iconic images of peasants tending paddy fields are paintings of Myanmar’s important seafaring communities. Set squarely in a mainly rural landscape are pictures of increasingly dominant cities. Nevertheless, at a time when much is changing in Myanmar, and equally much is not, these paintings also contribute to social and political documentation, and fill out the overall snapshot.

In the years leading up to and beyond a planned 2015 general election, Myanmar seems likely to press ahead with a broad programme of reform. As that happens, it will be painters as much as any other social group who measure the progress made in extending the boundaries of human freedom. Their aspirations are already abundantly clear. The issue to be addressed in the years to come is how fully they are able to deliver on them as complex processes of change play out across the country.

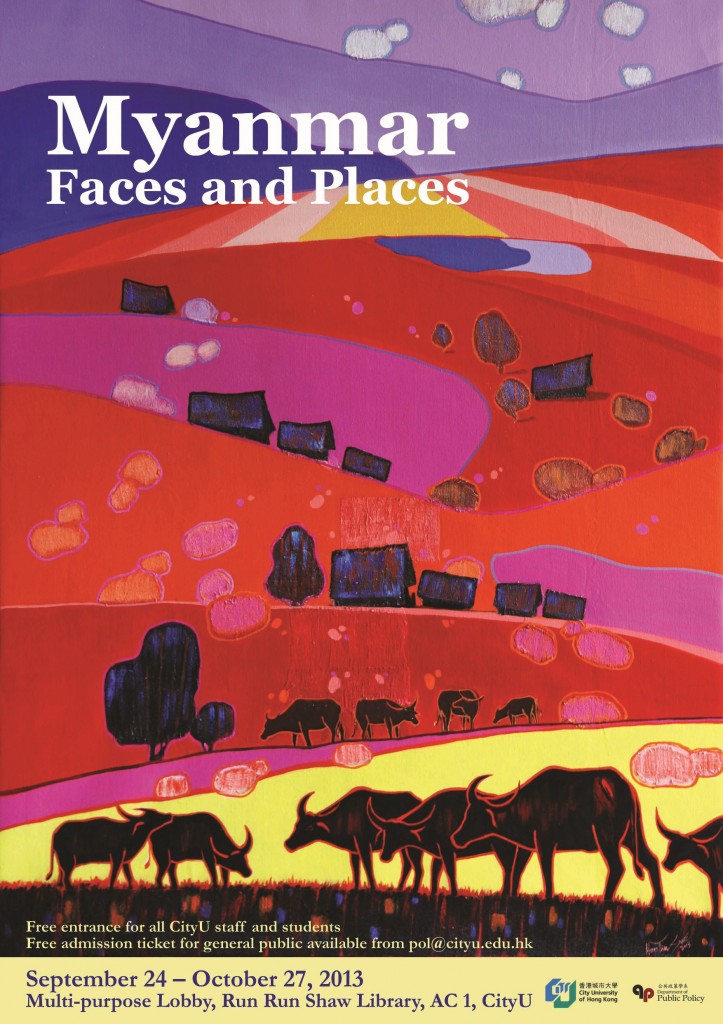

Myanmar: Faces and Places

City University of Hong Kong

September 24 – October 27, 2013

In Myanmar, a gradual removal of strict authoritarian controls over the past couple of years has enabled creative artists to give increasingly free rein to their talents. The weight of censorship was perhaps never quite as heavy for painters as it was for writers and film makers, because government officials typically had little understanding of their art, and limited concern about its political impact. Nevertheless, in the long dark night of state socialism from 1962 to 1988 and then military rule from 1988 to 2011, many subjects were taboo, many styles were frowned upon, and even some colours were banned. Today, almost all of these restrictions have been lifted, and any residual censorship is generally light-touch. At the same time, Myanmar’s rapid reopening to the outside world has triggered renewed global interest in its cultural landscape and heritage. The result is an explosion of artistry and flair inside the country.

The painters now emerging do not comprise a single generation. Indeed, even the sixteen artists brought together in this exhibition, all but one of whom are male, range in age from early twenties to early seventies. Nevertheless, there is clearly something of a cohort effect among present-day painters, focused on the major city and core artistic hub of Yangon. Within the conurbation, some artists have created an informal alliance, others have formed a mutual support association, many meet sporadically in downtown galleries such as Pansodan and Nawaday Tharlar, and still others are content to be loosely connected on the fringes of these overlapping networks. In an ever more liberal society, all are aware of advances made by fellow artists, and keen to learn from them in developing their own styles.

Equally, contemporary painters look to traditions stretching many centuries into the past. Nearly one thousand years ago, Bagan in the dry central plains of Myanmar became a key site in the evolution of Theravada Buddhism. Currently it boasts two thousand temples and stupas. Here line painting designed to instruct the faithful and gain merit for sponsors remains visible in both austere and exuberant murals painted in the earth tones from which natural pigments were made: black, brown, green, yellow, and deep red. From an animist spirit world came thirty-seven nats, god-like figures derived from historical beings held still to watch over human affairs. The minority ethnic nationalities found in contemporary Myanmar also generated distinctive cultures. All of these traditions provide inspiration for artists today.

Overlaid on these indigenous influences were pressures from outside. Some reach far back in time, for the land the British mapped as Burma in the mid-nineteenth century has long been shaped by the great Asian civilizations to the east and west of Myanmar’s current borders. More insistent in the past two centuries, though, were contacts with the West imported above all by Britain, which asserted imperial control over Burma through wars fought in 1824-26, 1852 and 1885. Colonialism introduced to Burma not only western cultural traditions, but also wealthy officials keen, in a small but significant number of cases, to encourage and support local artists. Eventually it also facilitated the spread of modernist ideas, though a progressively hostile climate after independence ensured that the imprint was never large. More recently, growing use of the Internet initially through cybercafés in urban areas and then through smartphones has delivered international influences directly into the country. Many contemporary painters draw on this eclectic mix in their work.

The result is that many ideas now swirl in cultural circles, and diverse artistic responses are made to the assorted reforms sweeping Myanmar. Some painters are openly political, and others make vague or obscure reference to current events. Most have no overt political intent, however, seeking simply to depict a society in which much is changing, but much is also largely unaltered. Together, the paintings assembled in this exhibition, all of which date from the current transitional era, thereby comprise important primary source material from a critical phase in the country’s history. While individuals in other walks of life attempt to capture the period in words, photographs, music and dance, painters portray it in pictures of faces and places that are stunning to behold, and intriguing to contemplate.

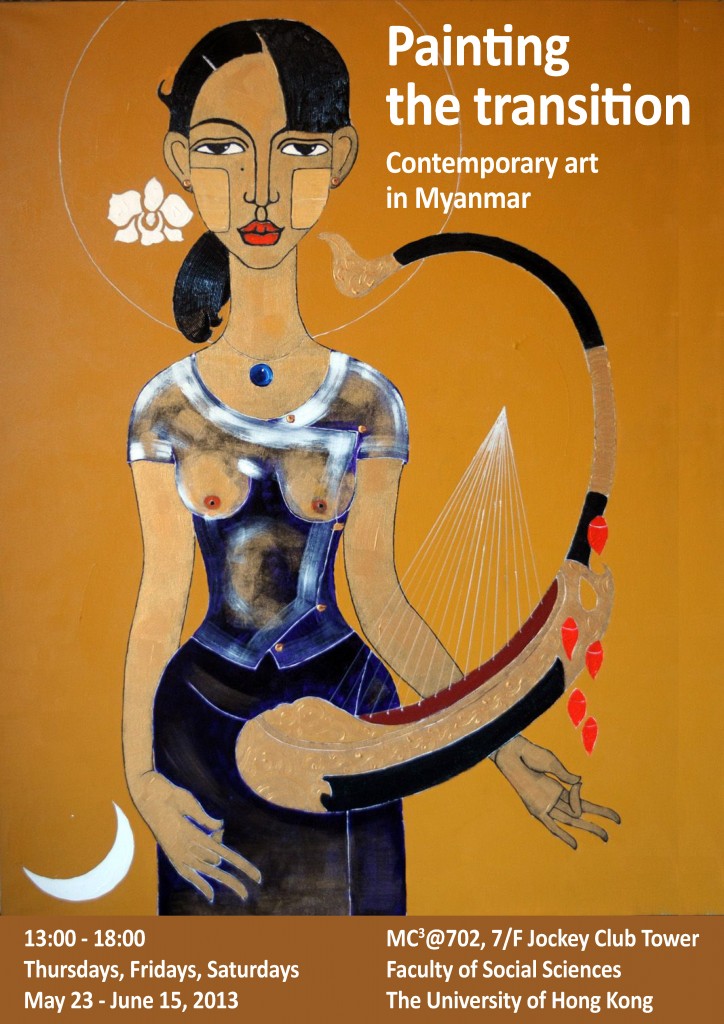

Painting the Transition: Contemporary Art in Myanmar

The University of Hong Kong

May 23 – June 15, 2013

Coming in from the cold after 50 years of austere dictatorship, Myanmar is currently testing the boundaries of a raft of new freedoms. Rigid controls were not dismantled overnight, but a March 2011 switch from military junta to quasi-civilian rule has slowly created space for meaningful self-expression. Finally people can breathe a little.

More than two years on, activists routinely take to the streets of major cities to protest government policy, journalists pursue breaking stories up and down the land, hawkers beguile tourists with long banned symbols of opposition, and ordinary citizens daily raise their sights just a little higher.

Playing critical roles in this outpouring of human creativity and energy are artists and intellectuals never fully silenced by authoritarianism, but certainly forced for years to operate below probing security radars. Today, by contrast, writers give readings at literary festivals, musicians perform rap and hip hop in concert, and painters exhibit canvases that for decades could be shared only with trusted friends.

Growing links with the outside world, dating from the late junta period, were important enablers of this renaissance. The arrival of internet cafes in major cities in the mid-2000s was notably important. Above all, though, change was driven locally as isolated groups of individuals formed for mutual support in teashops and restaurants built integrated and confident networks when political reform gathered pace.

One consequence of Myanmar’s cultural rebirth is that a significant number of artists can now work on a full-time basis. For leading painters, the change has been dramatic. Although the state ruled by generals generated jobs in illustration, graphic design and commissioned pictures for a small tourist trade, few could give free rein to their talent. Today an expanding group does precisely that.

Still conditions are not ideal. Some commercial galleries continue to flirt with state censorship. The major professional association is unreconstructed. The ponderous National Museum is off limits for most contemporary artists. Selling sufficient work to make ends meet is often a challenge. Nevertheless, the range and quality of art now being produced by local painters is astounding.

Accessed from a chipped concrete staircase in a crumbling colonial building, Pansodan Gallery in downtown Yangon is the hub for many new artists. Launched by husband and wife team Aung Soe Min and Nance Cunningham in August 2008, the gallery works proactively to connect painters with each other, and with potential buyers. It is also trying to launch an independent artists’ association.

Within the emergent band of painters some are openly political, espousing membership of a broad opposition movement. For them, independence hero Aung San, democracy icon Aung San Suu Kyi, and monks participating in the 2007 saffron uprising, all taboo topics until very recently, are now standard subjects. So too are oblique references to government failings and social problems.

More common across the new cohort, though, is a dual desire first to connect with the cultural heritage of a major artistic tradition, and second to bring it squarely into the contemporary age of sweeping social and political change. Buddhist symbols and ritual thus feature. Ethnic costume, music and dance are important themes. Customs and habits of village people in a still rural society are carefully represented. Changing rhythms of vibrant urban life are fully documented.

In these diverse ways, painters from Myanmar’s new generation of cultural and intellectual leaders provide nuanced and incisive commentary on a society embarking on what is certain to be a difficult journey. The start point was military dictatorship. The end point is unknown. Capturing twists and turns in the road is a network of accomplished artists emerging from a hermetic state.